Passing Project Revisited

The NHL season starts in a few days and this is the time of the year where my brain goes into overdrive with tracking games & getting the data out in the open. You’ll get hit with a barrage of stats, charts and tidbits from me and other analysts. You’ll hear lots of terms like “shot contributions,” “low-to-high passes,” “transition plays” and “high danger passing plays.” What do they all mean, though? Are they important or are they just fun stats to look at during games?

When you’re in the weeds, it’s easy to forget that everyone might not be familiar with the work you’re presenting and throwing 5-6 stats at once can be confusing. It’s also fair to question why I’m still doing manual tracking for hockey when we have stats like Expected Goals that do a better job of capturing on-ice & individual impact than the tools we had six years ago. For me, it’s just how I learned the game and being unhappy with the quality of data released by the league. We’ve gotten better at estimating the individual impact of players using play-by-play data, but I feel like manual tracked stats will always have their place in help explaining the “why” behind macro-level stats. Unless a play led to a goal, you’re generally in the dark about most events, except for whoever shot the puck. Was it off a passing play or did he carry the puck into the zone & beat a defender to generate the chance? Which one is better?

Most of the legwork was done back in 2015 by Ryan Stimson with his passing project and his initial observations revealed some cool things about offense in hockey. Some of it is very intuitive, like how a shot preceded by one pass alone has a small, but positive impact on a team’s shooting percentage (7.2% on unassisted shots to 8% with one assist). That number jumps to 9.6% when another pass is added to the sequence, which bridges the gap a little between expected goals & actual goals. Through his work, we also know that passes from behind the net lead to goals at a higher rate than other passing plays, most notably shots from the point (which are the lowest of low percentage shots). Things to help bridge the gap between transition stats like entries & exits have also been looked at by him, so there has been a lot of neat discoveries made through manually tracked data.

If there’s one thing I love about Ryan’s passing project, it’s that the tracking templates provide a lot of context and there’s so much information you can dig into even with just one game’s worth of data. Seeing which players assisted on shots & scoring chances would be a big help alone, but with Ryan’s data there is a lot more we can dive into. Passes can be broken down by which zone they originated from, the side of the ice they came from, the type of shot they setup (one-timer, deflection, slap shot, etc.) and the type of pass that occurred in some instances (stretch pass, cross-slot, behind net, etc.). You can really dive into the details of how teams create offense with this data. With the season about to start, I thought it would be a good idea to do an overview of the last four years of passing data I’ve tracked & see how it compares to Ryan’s initial findings from the 2014-16 seasons.

The Basics of Passing Data

Even with over 180,000 shots added to the database over four seasons, most of Ryan’s initial findings on the impact of a pass hold true. When factoring in rebound chances it’s especially true. Over the four seasons tracked, teams scored on 8% of their 5v5 shots on goal without a passing play. This is including rebound chances. If we exclude rebounds from this sample, that shooting percentage drops to only 4.1% out of all shots on goal. A rebound is recorded as an unassisted shot, but they are usually reactionary, second chance opportunities that are created off a shot from another teammate. They also come closer to the net & are a little different than your standard unassisted shots. Rebounds are also closer to the net and are somewhat difficult to track with 100% accuracy if you’re dealing with a situation where two or three players are going for the puck at the same time & are just jamming it into the goalie’s pads. All other unassisted shots had a shooting percentage of 5.6% or less, which goes to show the impact of just one pass. Yes, it’s only three percent but think of how many shots teams take in a year. Incremental improvements over time add up & that’s especially true when you consider that teams shot at 12.6% when they completed three passes before a shot on goal.

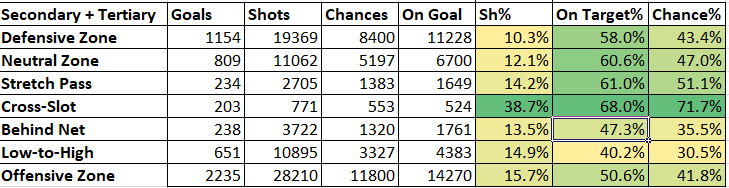

Another thing that holds with Ryan’s initial findings is the quality of certain passes.

All data is 5v5

What we’re looking at here is the location & type of primary assist for each shot taken in every game tracked since 2016 (1316 games worth). Also noted is the shooting percentage, as well as how often each shot resulted in a scoring chance or shot on goal. Finally, and most importantly, you’ll see the frequency of each passing play/type. There’s a textbook’s worth of information to take in here, so I’m going to break it down by the main points.

Royal Road & Behind Net Passes Still King

Going strictly from a percentage standpoint, the easiest way to boost your team’s goal total is to generate more passes from behind the net or create a cross-seam play to get the goaltender moving. The same rules in 2016 hold true today. The interesting part is how rare those plays are, as they account for only 13.2% of all shots (excluding unassisted ones). Let’s say a team averages 44-45 shots a game during 5v5 play, this means that only five of those will come of what are categorized as “high danger passing plays.” Ideally, you want to find players who generate these types of passes, as the payoff is huge. The problem is most teams can only complete 2-3 of these plays per game unless they’re playing Doug Weight’s Islanders or last year’s New York Rangers.

It’s not too surprising. Players are more skilled & quicker than ever, but defense is still the top priority for most teams and it’s hard to get a pass through the middle of the ice unless you have a superstar like Artemi Panarin in your back pocket. So few shots coming from plays behind the net is a little weird, though. If only because it’s easier to setup your offense from there or get a lucky bounce off a skate instead of trying to force feed a cross-rink pass through various layers of defense. This is where it would have been convenient to track attempted passes from these areas. I don’t have the patience to do this for all types of passes, but looking at the risk/reward factor for these plays would be interesting.

Do teams get burned more frequently if they miss on cross-seam plays or behind the net passes? Analysts will often gripe about players trying to be “too fancy” by looking for the cross-ice pass instead of taking the simple play. Sometimes forwards can get caught deep if two guys are behind the net, leading to a rush the other way, but is it any riskier than a shot from the point getting blocked? Ever since Ryan’s study, it felt like more teams were attacking from behind the net, but the overall frequency of these plays has stayed roughly the same throughout all four years. Maybe this suggests that more innovation can be done here. It would be interesting to see if there is a drawback to chasing these more dangerous plays while sacrificing shot volume.

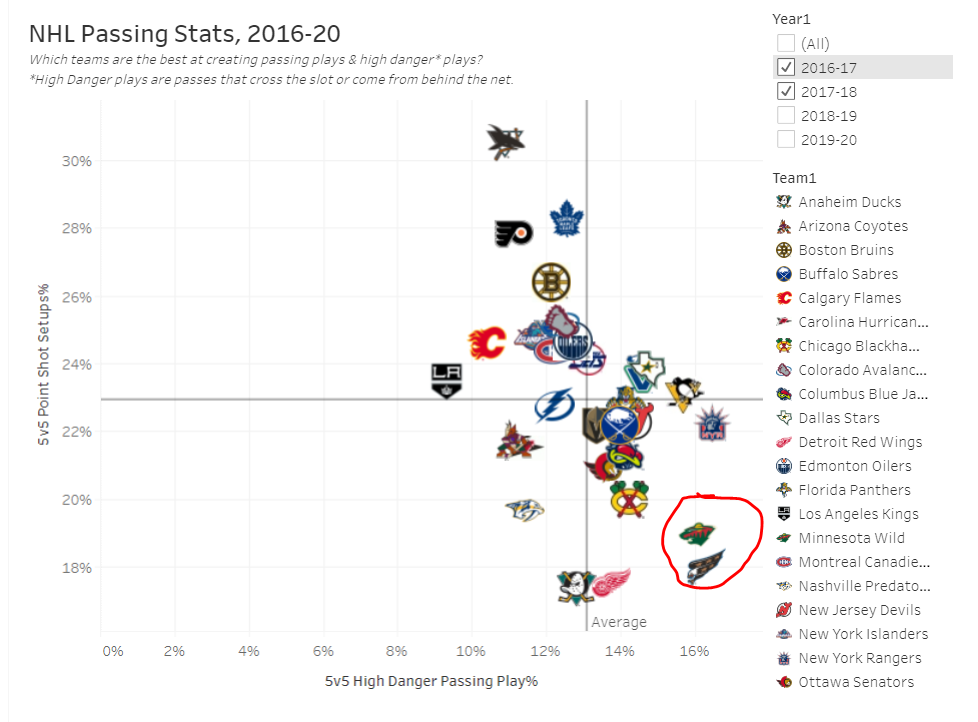

Some teams found success focusing on these plays, most notably the Minnesota Wild in 2016-18. They were a team that got outshot most nights, but were near the top of the league in terms of Expected Goals. They made the playoff both years, finished with over 100-points in the standings and were a strong 5v5 team in Actual Goal differential, as well. Looking at where their passing plays came from provides some insight into that.

Minnesota was a team that never shot from the points (at least not directly) and were one of the top teams in the league at working from behind the net or finding a cross-seam pass. It didn’t work for them in the playoffs, but they found some very good regular season success with this. I can’t speak to whether or not this was a strategic thing on Bruce Boudreau’s part, or him falling into a roster that had a bunch of very good players in their primes & him just rolling with it. Still, Eric Staal remembered how to score goals once he got there, Mikael Granlund had a couple of 40+ seasons after struggling to get to the next level, Charlie Coyle & Nino Niederreiter. They had a plan & got result. The Washington Capitals also had some success with this. Although on a much grander scale in 2017-18.

Cycle vs. Transition

If there’s one area that I’m still working to iron out with this type of tracking, it’s bridging the gap between zone entries/exits and the passing data. Looking at the table above, it looks like plays that happen in transition (stretch passes & passes from defensive or neutral zones) are low-percentage plays. A shot off a stretch pass is about as effective as a normal give-and-go pass and plays from the neutral zone don’t result in many goals either. This isn’t totally cut-and-dry, though.

Enough work has done been done to show that there is a huge difference between carrying the puck in and taking the shot or losing the puck & making a passing play after an entry. So much that I had to create a separate category for it in my own tracking. Regardless, the chart above isn’t the best proxy for transition because the better quality transition plays aren’t going to happen if the primary assist comes outside of the offensive zone (unless it’s a rare event like a breakaway or an odd-man rush, although most of those plays are generated in transition so this is another risk/reward convo). Think of your standard carried entry in hockey, something in the first five minutes of the game when both teams are getting a feel for each other. Something like this.

It’s a quick play meant to get a shot on goal or a puck battle, essentially. It goes down as a “transition play” and while that’s true, it’s not the most optimal play to create offense. Compare it to this rush from the same game & you’ll notice the difference in how it’s recorded.

Where does the primary assist occur? The offensive zone, specifically the middle lane, which is one area teams have done a good job of exploiting in this four year sample. It’s a rush play, but isn’t recorded as such, while in zone entry tracking it’s recorded as an entry with a pass. Then you have this, also from the same game.

Again, it’s a rush chance with the secondary assists happening up the ice & the main play coming after the entry. This is where we can bridge the gap. We know through Ryan’s earlier work that more passes equals better shots, how does that hold up with different types of secondary assists?

This feeds off what we talked about earlier. More passing plays in a sequence yields more goals but the reward from deeper passing plays isn’t as great as you’d think. At least compared to other sequences where 2-3 guys touch the puck before getting a shot on goal. This changes a little bit if it’s a stretch pass,* but the shooting percentage boost you get from these plays is in line with the other passing sequences listed. The one caveat here is that plays that originate from outside of the offensive zone produced a higher percentage of scoring chances, which could come down to an Expected Goals vs. Actual Goals debate & which you prefer as a coaching staff.

The one thing I will say about all of this is that it’s important to remember that offense isn’t a one-shot type of thing & happens in waves. Take the first Montreal goal I posted for instance. Good teams don’t let the play die in the offensive zone if the initial shot doesn’t work and can use these lower-quality shots to help setup better ones. This is where other pieces of the puzzle like Expected Goals & some of the newer forechecking stats can help. I’m not well versed enough coaching/tactics-wise to comment on the methods teams use here, but I’ve tracked enough hockey games to know that the NHL-level is a read/react game and teams will take what the defense gives them until something better opens up. Passing plays are one way to do that, but a quick shot to the net to break the structure is another way to get defenders out of their structure. Is it my preferred way? No, but it’s easier to execute for some teams. The hope is that playing the long game of recovering the puck &sustaining pressure will get the defense scrambling around, then you can set up your higher percentage plays.

This brings us to our final point.

*stretch passes are tracked when puck crosses two lines

Risks & Rewards of “Safe” Offense

If there is anything that stood out to me, it’s how often teams still revert to point shots for offense. Over 22-percent of all primary shot assists were low-to-high plays, which are essentially point shots that have roughly a 2-percent chance of resulting in a goal. These shots even getting on goal is a crapshoot because unless you’re shooting from 40 feet away on an unscreened goaltender, the puck has to travel through layers of bodies, traffic and other layers of defense. It’s the definition of a low-percentage play & an uncreative way to run your offense.

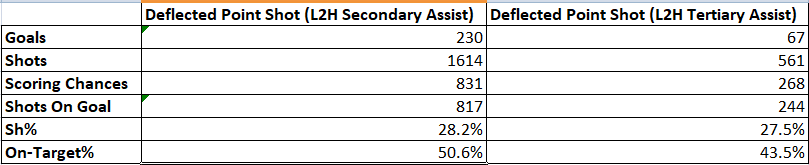

So why do teams revert to this? It goes back to a few things we discussed earlier. Hockey is a read/react type of game and most of the open space in the offensive zone is going to be up high where the defensemen are. You have more time & space to operate from up high and sometimes the only play available is to take the shot. It doesn’t mean you should do it, but in the heat of a moment during a game, reverting to the safe option is pretty normal. Scoring directly off the point shot also isn’t the primary objective, as you are usually hoping to score off a deflection or a rebound. How does that compare to, say, trying to setup from behind the net? From a shooting percentage standpoint it’s an interesting tradeoff.

Deflections & rebounds have the highest conversion rate out of all 5v5 shots tracked, shots that are deflected having a 29.9 shooting percentage and rebounds having a 23.4 shooting percentage respectively. The chart above scales it down to deflected shots where a low-to-high passing play was involved in the sequence, which means the first column is mostly deflected point shots (unless the player covering the point creeps down the wall to make the play like Jake Gardiner does on the first goal in this video) while the second column shows ones with more puck movement up high (d-to-d passes, low to high movement on the wall, etc). Regardless, roughly the same when a team successfully gets a deflection goal. You get a decent scoring chance that about a 50-50 chance of getting on goal, which doesn’t sound that bad compared to some of the other options listed.

The issue with this is that we’re only looking at successful tip plays. If a team is attempting this setup & misses, what are you left with? A simple point shot that has less than two percent chance of finding the back of the net. Out of all 5v5 shots tracked that involved a low-to-high sequence, only eight-percent of them resulted in a deflection. So, while a deflection is a high-danger chance, generating them is tough and most of the time you’re just settling for a low-percentage shot. Combine that with shots off low-to-high passes only reaching the net 35-percent of the time, and it’s a tough way to win if that’s the only way you can create offense. The scarcity of goal-scoring in the NHL might encourage this type of hockey, but I still think more can be done with how skilled players are now. Hockey has a lot of randomness & chaos to it, so banking on point shots, rebounds & deflections for your offense is just adding to that and

That being said, moving the puck up high can still be used as an effective strategy for creating offense, it just has to be part of a sequence instead of the final play. That or it’s part of a chain where you’re eventually working up to set a better play. The Tampa Bay Lightning last year were a good example of this. Over 26-percent of their shots came off low-to-high plays, which was the third highest in the league. They scored a grand total of zero goals off those plays. So, how did it work for them?

It’s a combination of things. They’re a team that can win with shot volume and while they settled for low-percentage plays, they were very good at getting the puck back & sustaining pressure in the offensive zone to setup something better. Despite their high-end skill, they’ve been roughly league average on creating high danger passes to setup their shots the past two years. The fact that they’ve been so good offensively despite this just shows how creative the Lightning are and how they don’t give defending teams one area to key-in on.

There are a lot of factors that go into this. Most of their shifts will look like this.

This is mostly an inconsequential shift because the Wild defend it well, but the one thing I want to focus on is how the Lightning just kept getting the puck back. Taking quick routes to disrupt exits and having a forward play above the play so that it’s tough for the Wild to get out of the zone. The Lightning didn’t generate a chance here, but this is what most of Tampa’s shifts look like when there isn’t much space to work with. They’ll play the territorial game & just keep putting pressure on the team exiting the zone, so that they can’t get a rush going the other way.

Eventually, they can setup something like this.

Again, offense happens as a chain and the Lightning show it well here.

Conclusions